Description

Fretting is the degradation of surfaces in close contact subjected to relatively small reciprocating movement e.g. from vibrations. The movement between the surfaces may be as low as 5nm.

This mechanism can occur in assemblies where the surfaces in contact are assumed to be fixed and not expected to exhibit wear.

Mechanism

The relative movement between two surfaces in contact can start to generate damage with small particles of material breaking away. These may then oxidise and act as an abrasive at the interface of the surfaces which in turn leads to more fretting damage. With time the damage rate increases. Fretting can also occur without oxidation or corrosion of the wear debris.

Fretting damage can occur in multiple applications including gears and other similar components mounted on axles or shafts, the anchor point of turbine blades in a gas turbine, and on electrical contact surfaces.

The interface between a component such as a wheel or gear mounted on a shaft will often be a ‘tight’ fit. This may be a sliding fit or interference fit where the dimension of the shaft journal is slightly larger than that of the bore in the mating component. A compressive load is then induced in the shaft with a corresponding tensile load in the mating component. This fit is designed to prevent movement between the two components. Fits with less interference may also include the use of a key to prevent rotational slippage of the components, and providing a route for the drive between shaft and component. Loading on the components can cause microscopic movement between the surfaces but rather than the whole surface moving, stresses and strain in the materials may cause movement at the extremities of the interface and not at the centre.

With the development of fretting, the surfaces are damaged leading to increases in clearance, and the worsening of the surface texture (roughness). Fretting surfaces are known to then initiate fatigue cracks. The crack will typically initiate at a shallow angle, following the orientation of the damaged surface material, and once it reaches the unaffected substrate material, it will propagate at an orientation perpendicular to the principle stress direction, often at right angles to the surface.

Appearance

On ferrous components, even stainless steels, the fretting wear debris will typically corrode/oxidise generating a characteristic red-brown powder as shown in the image below, showing a heavily fretted shaft. This shaft had fractured due to the propagation of a corrosion fatigue crack.

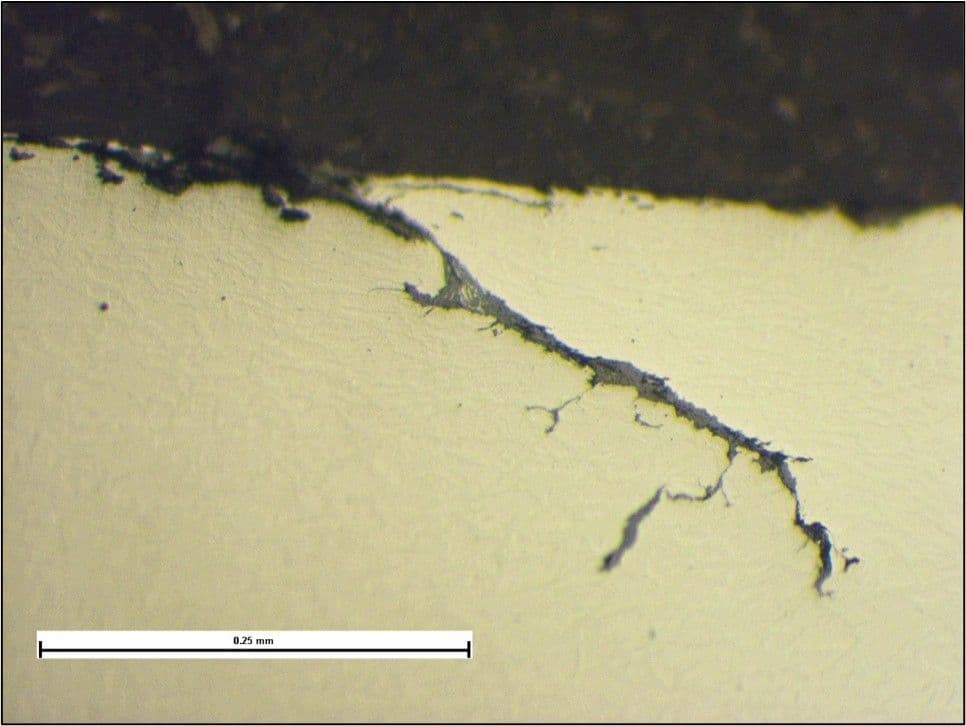

The examination of a section through the fretted surface revealed multiple secondary corrosion fatigue cracks as illustrated in the image below. The crack is orientated at approximately 45° to the surface of the shaft, which is common for fatigue cracks that initiate on a fretted surface, and the crack tips are starting to reorientate to be perpendicular to the axis of the shaft.

The image below shows the bearing surface from the axle of a high-performance car used for racing.

The axle had fractured due to the propagation of fatigue cracks elsewhere on the axle, remote from the fretting. However, the extent of the fretting shown here indicated that the axle had probably been exposed to higher than expected stress, which may to some degree not be unexpected for the application. The increased clearances produced by the fretting damage then increased cyclic stresses within the axle, which then caused its fracture by fatigue and loss of the wheel during the race.

Mild or early stage fretting may just exhibit light debris, but again, with a characteristic red or orange-brown deposit as shown on the inner circumference of the bearing race shown below.